Building capacity in Northern Australia

25 Oct 2024Northern Australia holds a special place in my heart and not just because I call the north home. Northern Australia has a beautiful, vast coastline that stretches approximately 10,000 kilometres. This sparsely populated coastline is the frontline for several emergency animal disease (EAD) threats which could reach the Australian coast through the movement of people and goods by sea or air, or animal migration.

Our near neighbours, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Timor-Leste have a different health status to Australia which means that traditional trade pathways, illegal vessel movements and even insect vector dispersal leave northern Australia vulnerable to an EAD incursion. This is why it is so important to ensure that northern Australia is resilient to threats posed by EADs – both in ability to detect disease and in ability to respond and recover.

It could be said that I forged my career working in the north. I certainly spent my fair share of time living and working in Queensland and the Northern Territory. Perhaps that’s what sparked my passion for the region. Whatever the case, following my then appointment as Deputy Australian Chief Veterinary Officer in 2022, I was excited to return to the north and establish and lead a Northern Australia office. It was a great opportunity which positioned me as the primary technical advisor on animal health and EAD preparedness across northern Australia for the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. The role also allowed me to lead the department’s work strengthening engagement and capacity building in the region.

In my role as Australia’s Chief Veterinary Officer, I remain committed as ever to northern Australia. We continue to focus on building the north’s resilience against EAD threats through provision of a strong Australian Government presence and strong partnerships, including active engagement with animal industry groups and First Nation’s stakeholders. My office promotes capacity building around prevention, preparedness, detection and response to EAD threats such as foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) and lumpy skin disease (LSD) both in near neighbours and northern Australia. This continues the department’s focus on northern Australia as a priority area for biosecurity.

Ongoing work in the north

The Northern Australia Quarantine Strategy (NAQS) is potentially the most well-known area of the department when it comes to biosecurity activities in the north. It has been in operation for 35 years! I fondly remember my time as a field veterinarian and project manager with NAQS and continue to enjoy watching the program evolve over time.

NAQS continues to provide an early warning system for exotic pest and disease detection through animal and plant surveillance in the north. In the space of animal health surveillance, one aspect of their work is targeted surveillance for a range of exotic animal diseases including avian influenza, FMD, LSD and African swine fever (ASF). A small team of NAQS field and policy veterinarians, in collaboration with Indigenous Rangers and pastoralists deliver these surveillance activities. NAQS also manages biosecurity risks associated with movements between the Torres Strait and mainland Australia, works closely with key stakeholders such as First Nations communities and participates in surveillance activities in near neighbour countries to enhance regional animal health systems.

Figure 1: NAQS officers in the field (Source: Dr Guy Weerasinghe, DAFF)

Strengthening northern networks

As the largest agriculture industry in northern Australia, the beef cattle industry is one of our key stakeholders and biosecurity partners. My office maintains strong working relationships with key stakeholders such as AgForce Queensland, the Kimberley Pilbara Cattlemen’s Association and the Northern Territory Cattlemen’s Association. Industry has demonstrated a strong and active commitment to animal biosecurity by collaborating on EAD awareness initiatives. This joint effort is essential in fostering a shared responsibility for biosecurity, and their contributions are well recognised both in northern regions and at the national level.

First Nations peoples have a deep-seated connection to the land and sea, and it is important to recognise that their traditional knowledge helps protect Australia from the threat of biosecurity incursions. My office is developing strong connections with First Nations communities via the Indigenous Biosecurity Ranger program and Biosecurity Engagement Officers through NAQS. I am proud that my office is increasingly working with First Nations representatives on projects to address northern Australia’s vulnerabilities to EAD threats.

We also, of course, continue to work very closely with our state and territory colleagues. My office contributes to several groups and committees seeking to enhance capacity against EADs in the region. This includes the Northern Australia Biosecurity Surveillance Network (NABSNet), the Northern Australia People Capacity and Response Network (NAPCaRN) and the Northern Australia Coordination Network (NACN).

NABSNet and NAPCaRN were established under the Northern Australia Biosecurity Strategy 2030. NABSNet connects private veterinarians who service northern Australia with government and promotes relationship building with producers through investigation of significant disease incidents and skin surveys to support our evidence of freedom from LSD. Meanwhile, NAPCaRN aims to bolster First Nations and industry capability through the addition of technical officers, interns and liaison officers based in the north to enhance surveillance, engagement and diagnostic capabilities. My office is also a member and provides secretariat support to NACN. NACN was established for a two-year period to enhance preparedness against the threat of EADs such as FMD and LSD. The network includes government representatives from Queensland, the Northern Territory and Western Australia and the northern livestock industry associations.

Australia’s animal health system is founded on biosecurity partnerships. These partnerships are more important than ever in Australia due to the rising risk of EADs in the face of global change.

Connections within Australia and beyond

Northern Australia faces unique challenges that could affect the entire country’s ability to prepare for and respond to EAD threats. Remoteness, seasonal accessibility issues, difficulties managing feral and wild-roaming animal populations, workforce shortages and the impacts of climate change are a few of these challenges.

My office continues to play an important role identifying potential vulnerabilities to EADs across the north and supporting resilience in the area against EAD threats, including ensuring representation at a national level. A prime example of an EAD which has been identified as a significant risk to Australia is highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1. HPAI H5N1 has had unprecedented global impacts on agriculture, environment and human health sectors. Currently, Australia and Oceania are the only regions free from HPAI H5N1, however we must be prepared for the possibility it will enter Australia – potentially through the north. The Australian Government’s investment in our biosecurity system ensures that our well-established national arrangements and One Health approach to managing biosecurity challenges such as HPAI H5N1 positions us well to tackle any possible incursion.

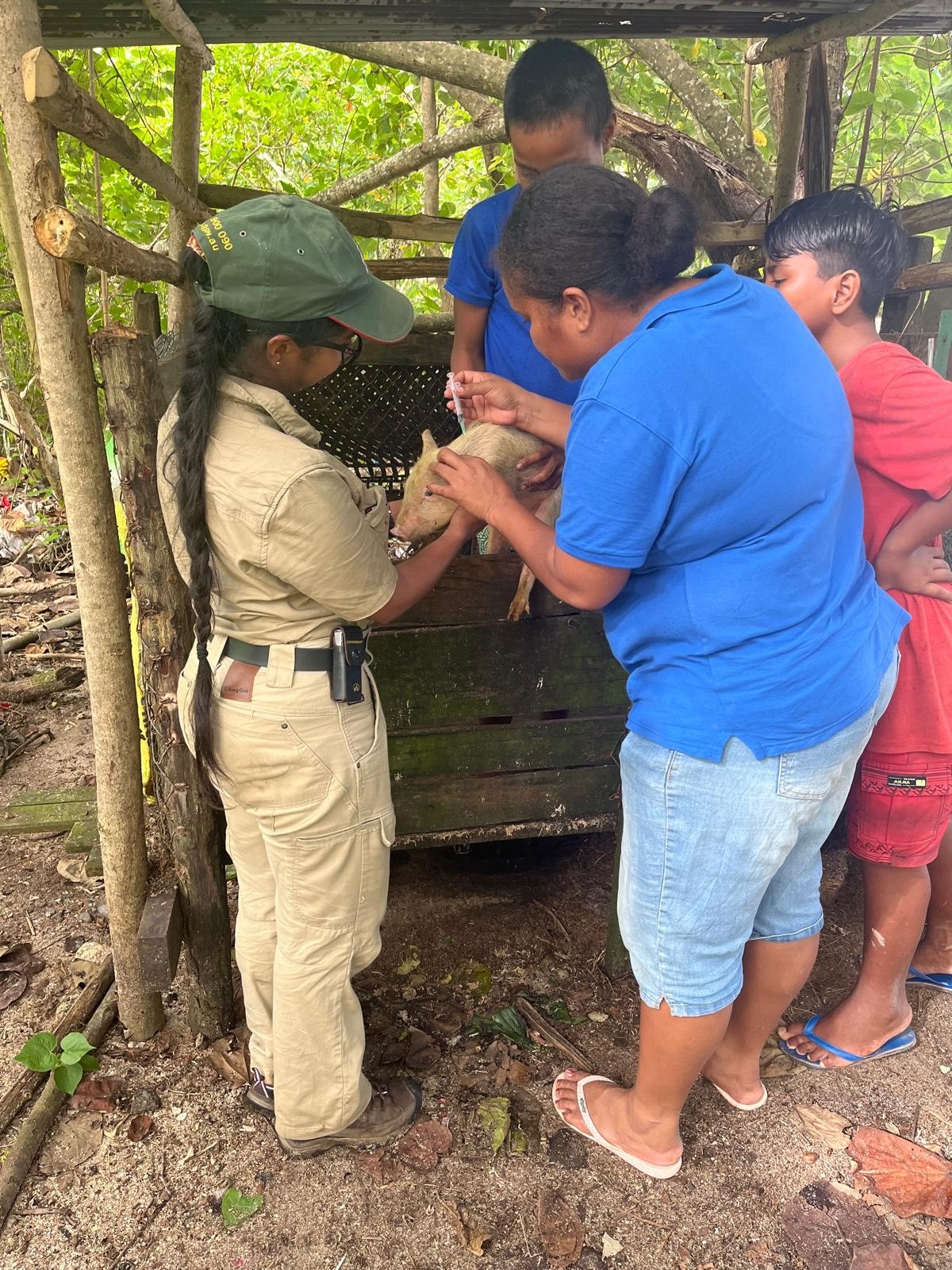

Effective biosecurity management requires a cooperative approach that extends beyond our borders. The department is committed to collaborating with neighbouring countries to enhance animal biosecurity throughout the region. Policy and veterinary officers from my office actively assist our neighbours with animal disease preparedness and response activities to enhance regional animal biosecurity systems. This work is critical in protecting the livelihoods of the communities that depend on healthy animals for their main source of income and for food security. Our work includes capacity building partnerships with Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea to support preparedness and response to ASF, FMD and LSD. In south-east Asia, my officers worked with other Australian Government agencies and industry partners to support Indonesia’s response to LSD and FMD.

Figure 2: Offshore capacity building activities (Source: Dr Dan Edson, DAFF)

Biosecurity plays a critical role in reducing risk and maintaining Australia’s status as one of the few countries in the world to remain free from the world’s most significant animal diseases and pests. Ongoing vigilance and collaboration both within Australia and internationally is essential in maintaining this status and the many benefits it affords us all.

Working in the north can be incredibly challenging, but from personal experience, I know that it’s also immensely rewarding and offers unique opportunities for veterinarians. If you would like more information on EAD threats to Australia, including the north, please download Emergency animal diseases: A field guide for Australian veterinarians.

For the latest updates on the work of the Office of the Chief Veterinary Officer, please follow the social media channels of the Australian Chief Veterinary Officer on Twitter/X and LinkedIn.